Lately, on Learning to Listen, we've been focusing on musical form - the blueprints that composers use to make a piece of music. If you'd like a reminder on what form is, check out the Introduction to Musical Form episode here on classicalmpr.org.

This lesson focuses on the term 'rondo'.

The rondo was fairly ubiquitous throughout the Classical era (toward the end of the 18th and early years of the 19th century). Composers like Mozart and Haydn and Beethoven all loved the rondo form and used it often. But way before those guys, as much as a century or two earlier, J.S. Bach, Lully, Couperin and even Monteverdi wrote rondos.

So. What's a rondo? I like to explain rondo by using fruit. Here's why.

If we lay a bunch of fruit in a line the way a composer lays out musical ideas for a rondo, we'd have the following in front of us: an Apple, a Banana, an Apple, a Clementine, an Apple, a Banana, and an Apple.

Do you see the pattern there? We put an apple between every other piece of fruit. The apple represents the primary musical ideas of the piece. Once the composer presents those ideas, he or she moves on to the banana ideas. Once we're done hearing the banana ideas, we go back to hear the apple ideas again. But the rondo keeps going and then it's time for the Clementine, followed by another apple; then the banana, and finally another apple. We always go back to the apple after we're introduced to new fruit.

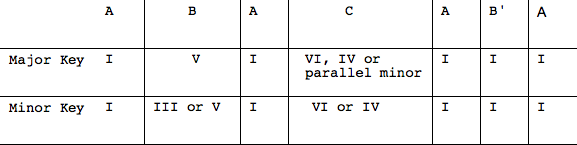

If you're not much of a fruit person, you could picture a rondo as a chain of letters: A B A C A B A. The A always comes back before we hear another letter - or in music, before we hear new material.

Why would a composer want to repeat the apple or the A material over and over? Isn't that really repetitious? What works about a rondo? The A material becomes familiar through its repetition; the art of a rondo involves straying from that A material and taking the listener elsewhere before returning us to that familiar aspect; the A material.

Letters and fruit aside, listen to the audio above to hear how Beethoven created a rondo for the final movement of one of his first real hits - his Piano Sonata No. 8 called the Pathetique.

Love the music?

Show your support by making a gift to YourClassical.

Each day, we’re here for you with thoughtful streams that set the tone for your day – not to mention the stories and programs that inspire you to new discovery and help you explore the music you love.

YourClassical is available for free, because we are listener-supported public media. Take a moment to make your gift today.