Believe it or not, in 1880 Richard Wagner seriously considered immigrating to Minnesota. That year his wife Cosima dutifully noted in her diary that Richard was pouring over maps of our state.

As early as 1849, Wagner had his eye on the United States. After all, in the view of many 19th century Europeans, that's where the money was. As Wagner put it in a letter he wrote in Zurich, where he was living in exile after participating in the failed Dresden Revolution of 1848, "America for me now and always can be only of financial interest."

Just three years later, he would write that while he was working on his opera projects in Europe, he was toying with the idea of staging them elsewhere: "I am now thinking a good deal of America! .... The ground there is easier to plant ... I am planning to make a start soon on my great Nibelung trilogy. But I shall perform it only on the banks of the Mississippi."

His friend, fellow composer, and eventual father-in-law Franz Liszt tried to dissuade him, writing, "Quite honestly, I do not think much of your American ideas."

Wagner's long-suffering European patron, King Ludwig of Bavaria, pleaded, "I implore you by the love of friendship ... to abandon this dreadful plan ... Your roses will not grow on America's sterile soil, where selfishness, lovelessness, and Mammon hold sway."

Wagner kept dreaming of striking it rich in America, however, and in 1880 asked his family dentist, one Newell Jenkins, who happened to be an American, to run an offer by some rich Americans and see what they thought of it. For one million dollars and the establishment of an "American" Wagner Festival like the one in Bayreuth, Wagner would come to America and premiere his latest opera, Parsifal, on the banks of the Mississippi.

A Wagner Festival in Winona, perhaps?

As might be expected, even Wagner enthusiasts in America thought this, as one 1880 contemporary musical commentator put it, an "almost insane proposal."

Dr. Jenkins, between probing Wagner's molars, must have broken the news to him that there would be no one million dollars waiting for him in Minnesota. One million mosquitoes, yes — but dollars, no.

Wagner never came to Minnesota, but his operas did.

Wagner operas in Minnesota, 1887 to 1988

In 1887, just seven years after Wagner's musings about coming here himself, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin became the first Wagner operas to be staged in Minnesota — at the old Grand Opera House in downtown Minneapolis at 6th and Nicollet (no longer standing).

They were performed by an enterprising touring company called the National Opera, who sang everything in English. This group was founded in 1886 as the American Opera Company by Jeannette Thurber, the same wealthy patron who started the National Conservatory in New York City where Antonin Dvorak taught. The names of the 1887 National Opera performers are not familiar ones these days, but back then some of these same singers also appeared in leading Wagner roles at the Metropolitan Opera.

It was New York's Metropolitan Opera that brought Tannhäuser and Lohengrin back to Minneapolis as early touring productions in 1900. These were staged at the old Industrial Exposition Building, which once stood close to the east side of the Mississippi in Old St. Anthony Main. These 1900 touring performances featured Golden Age Met singers, including sopranos Johanna Gadski and Lillian Nordica, alto Ernestine Schumann-Heink, and bass Pol Plancon.

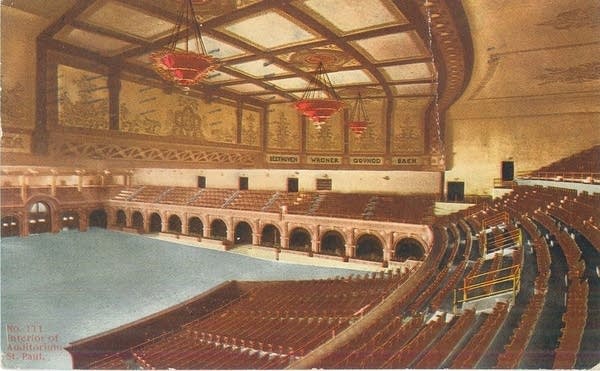

The Met's second touring performances of Wagner's Tannhäuser and Lohengrin took place across the Mississippi at the old Saint Paul Auditorium, in April 1907 and 1910, respectively, with casts including famous Met singers like soprano Emma Eames and alto Louise Homer.

The Met brought Wagner's Parsifal here in 1905, for a touring production at the old Minneapolis Auditorium at 11th and Nicollet, with a local favorite, soprano Olive Fremstad, singing the role of Kundry. Although Fremstad was born in Stockholm, she was considered a home-town gal, since she had moved to Minneapolis at the age of 12 with her adoptive American parents. Fremstad served as the real-life model for Thea Kronborg, the heroine of Willa Cather's novel The Song of the Lark.

From 1945 to 1984, Northrop Auditorium on the East Bank campus of the University of Minnesota was the venue for the Met Opera's subsequent summer tour productions of Wagner operas. Oddly enough, Wagner's Die Walküre, the second opera in his Ring cycle, was staged as part of the Met's very first Northrop season in 1945 (with famous Wagner sopranos Helen Traubel as Brünnhilde and Astrid Varnay as Sieglinde), and also as part of its very last Northrop season in 1984 (tenor Jon Vickers sang Siegmund, and James Levine conducted).

In 1974, the ambitious — and short-lived — Saint Paul Opera Company staged Wagner's Siegfried, the third opera in Wagner's Ring cycle, in Minnesota. That performance took place at the O'Shaughnessy on the St. Paul campus of St. Kate's, and was sung in the English translation prepared by Andrew Porter.

As far as the other operas in Wagner's Ring cycle are concerned, the Twin Cities have seen no complete, staged performance of Götterdämmerung, the grand finale of Wagner's Ring cycle, but the Minnesota Orchestra did present a complete concert performance of Das Rheingold, the first opera in the cycle, back in 1988. That was conducted by Edo de Waart, with the role of Loge sung by the famous East German tenor Peter Schreier, and a young Debbie Voigt featured as one of the three Rheinmaidens. Update: See note at end of feature.

This year, the Minnesota Opera is bringing Wagner's Das Rheingold to life at the Ordway Center for the Performing Arts. Is this perhaps the start of a complete Ring cycle in St. Paul?

If so, perhaps Wagner's wild dream of bringing his complete Ring cycle to the banks of the Mississippi might finally again be realized.

Update 11/14

When I pulled together this information for my own interest, I missed the important earlier research on this subject published by John T. Sielaff in the newsletter of the local Wagner Society. The history is even more fantastic than I could have imagined!

Astonishing, considering the Great Depression had just begun: another touring company brought a staged production of the entire Ring cycle to St. Paul in 1930.

As John T. Sielaff puts in his feature:

"The German Grand Opera Company first appeared in January of 1929 in New York heralded by an advertising campaign featuring huge billboards promising 'all the traditions of the Bayreuth Festival' in uncut performances of Wagner's music dramas. Using singers from German Opera houses, and famous soprano Johanna Gadski heading the casts, many tickets were sold in advance to New York Wagnerites ...

"With [concert promoter Sol] Hurok in charge and a less ambitious mandate, this company toured the United States in the early 1930s bringing Wagner's music dramas, including the Ring cycle, to over 20 cities. So it was that the Ring cycle came to St. Paul in February of 1930 and the following year The Flying Dutchman, Tristan and Isolde and Götterdämmerung were performed. And the Women's City Club of St. Paul made a profit in sponsoring the performances ...

"To bring the troupe here the Club had to send an advance of $20,000 which they raised through advance ticket sales. In order to make a profit the Club needed to sell out the new 3,100 seat St. Paul Auditorium. Tickets for the 1930 Ring Cycle ranged from $250 to just $5. Yes, $5.00 to see the entire Ring. The investment paid off when the Ring performances netted $8,730 for the building fund. The 1931 season brought in an additional $12,000."

So I stand happily corrected by Mr. Sielaff's research: it now appears all of Wagner's opera were staged in the Twin Cities at least once, and the Ring did make it to the banks of the Mississippi in 1930 — thanks to the enterprising fundraising and marketing of the Women's City Club of St. Paul!

John Michel worked at MPR from 1977 to 1995, and currently is the membership director at the American Composers Forum. He writes the scripts for Composers Datebook, hosted by John Zech, which airs on MPR and is distributed by American Public Media to many other public radio stations across the country.

Love the music?

Show your support by making a gift to YourClassical.

Each day, we’re here for you with thoughtful streams that set the tone for your day – not to mention the stories and programs that inspire you to new discovery and help you explore the music you love.

YourClassical is available for free, because we are listener-supported public media. Take a moment to make your gift today.