The way Tom Mullon sees it — the way he hears it — four musical notes can sum up a life.

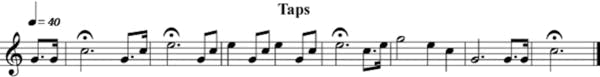

Four notes, arranged into a simple melody of 24 tones, played by a solitary bugler, might be one of the nation’s most recognizable and enduring pieces of music: “Taps.”

Mullon, 84, is among the buglers who nearly every weekday sound “Taps” at Fort Snelling National Cemetery, next to Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport — as many as 18 times a day.

“I think of ‘Taps’ as a pattern of life,” says Mullon, who for 20 years has played “Taps” for thousands of military funerals at Fort Snelling. “The first three notes [represent] birth. The next three are growing up.”

Listen: ‘Taps’

The next nine reflect schooling and maturity, and the following three-note ascent to a single high note are a person’s peak years.

“Then you come down slowly, and the last three notes are the passing on,” he says. “I try to make the last note fade off.”

Mullon doesn’t make a big deal of his “Taps” interpretation: “If I want to be a tough guy, I don’t bring that up.”

By law, a deceased soldier, sailor, airman, Marine or Coast Guardsman is entitled to a two-person uniformed honor guard, a rifle squad, a burial flag and the playing of “Taps.” Typically, a small bus shuttles the riflemen and bugler from funeral to funeral among the 246,000 graves in the cemetery’s 434 acres.

As family members and friends gather under an open-air shelter, a flag that has draped the casket is folded and presented to a family member. A five-member rifle squad fires a volley of three shots. Then comes the sounding of “Taps,” which first was heard in July 1862 in Virginia during the Civil War.

Mullon, former director of the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Minneapolis, sometimes blows a bugle, sometimes a trumpet. Usually he plays on Fridays, which tend to be busier because weekend funerals often are scheduled for the convenience of out-of-town travelers.

Sometimes he plays on scorching hot days; sometimes in below-zero cold, when saliva can freeze in the trumpet valves. He has learned to wrap his mouthpiece in a hand warmer and keep it in his pocket. Even so, he usually plays trumpet in the summer and a bugle — no valves — in the winter.

Whatever the season, he remembers which direction to face.

“Do not play ‘Taps’ into the wind,” he says. “The wind is stronger at the cemetery. It’s all flat, and the wind comes whipping across, and it blows the air back into your mouth.”

That makes it tough to play each note perfectly.

“If I miss a note, I hear about it,” he says, from his fellow squad members, all of them military veterans. “We’re very hard on each other.”

He remembers hearing Keith Clark, the Army bugler at the 1963 funeral for the assassinated President John F. Kennedy, muff the sixth note of “Taps,” which actually gave Mullon satisfaction because it showed how the solemnity of the moment can affect a musician.

“‘Taps’ is a very emotional song,” he says. The 24 notes “all kind of fit together. It has some feeling. That guy was choked up.”

Mullon tries to prevent such moments by practicing with a muted trumpet in his basement.

“I don’t practice as much as I should to keep the lip limber,” he says.

But even when a performance isn’t perfect, he agrees with the Army’s insistence on using live buglers instead of electronic attachments that fit on the end of an instrument and play “Taps” when a switch is flipped.

Joe Collova, a retired Marine who, with Mullon, often plays a two-horn version of “Taps,” recalls hearing of a funeral service when the battery on an accessorized trumpet died.

“That’s kind of embarrassing,” he says.

The two-bugle “echo” version that Mullon and Collova perform is not officially approved at military funerals but often is played anyway; people like the harmony.

Collova owns seven trumpets and keeps them where he is most likely to perform — at a cabin up North, at his church and in his car, along with a veteran’s cap. He once was driving in St. Paul on an anniversary of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and noticed a building with a half-mast flag flying out front. He stopped and realized the building was a junior high school. He went inside and got permission for students to come outside and listen while he played “Taps.”

“You’ve got to keep the memories alive,” he says.

Mullon and Collova also perform at events arranged through the nonprofit Buglers Across America — Memorial Day observances, for example, or at fundraisers. The nonprofit organization was created 20 years ago to make sure “Taps” is played by a live musician, not by electronics — “powered by heart rather than by batteries.”

There are no women among the trumpeters at Fort Snelling, but Mullon says they would be welcome if they know the music and can play it appropriately. Musicians and riflemen are not paid for their funeral duties.

Collova, 72, says he has played for 15 years simply to honor the service members who have passed. He doesn’t plan to stop any time soon but wonders how his service will end. He knows a bugler who lost his teeth and could no longer play a horn. Another began to suffer a mental decline and had to quit.

“I’ve played it hundreds of times,” he says. “But someday will I forget ‘Taps’?”

This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota Legacy Amendment‘s Arts & Cultural Heritage Fund.

Love the music?

Show your support by making a gift to YourClassical.

Each day, we’re here for you with thoughtful streams that set the tone for your day – not to mention the stories and programs that inspire you to new discovery and help you explore the music you love.

YourClassical is available for free, because we are listener-supported public media. Take a moment to make your gift today.